2003 Invasion Of Iraq (page 2)

Casus belli and rationale

George Bush, speaking in October 2002, said that "The stated policy of the United States is regime change... However, if Hussein were to meet all the conditions of the United Nations, the conditions that I have described very clearly in terms that everybody can understand, that in itself will signal the regime has changed".[68] Citing reports from certain intelligence sources, Bush stated on 6 March 2003 that he believed that Hussein was not complying with UN Resolution 1441.[69]

In September 2002, Tony Blair stated, in an answer to a parliamentary question, that "Regime change in Iraq would be a wonderful thing. That is not the purpose of our action; our purpose is to disarm Iraq of weapons of mass destruction..."[70] In November of that year, Blair further stated that, "So far as our objective, it is disarmament, not régime change – that is our objective. Now I happen to believe the regime of Saddam is a very brutal and repressive regime, I think it does enormous damage to the Iraqi people... so I have got no doubt Saddam is very bad for Iraq, but on the other hand I have got no doubt either that the purpose of our challenge from the United Nations is disarmament of weapons of mass destruction, it is not regime change."[71]

At a press conference on 31 January 2003, Bush again reiterated that the single trigger for the invasion would be Iraq’s failure to disarm, "Saddam Hussein must understand that if he does not disarm, for the sake of peace, we, along with others, will go disarm Saddam Hussein."[72] As late as 25 February 2003, it was still the official line that the only cause of invasion would be a failure to disarm. As Blair made clear in a statement to the House of Commons, "I detest his regime. But even now he can save it by complying with the UN's demand. Even now, we are prepared to go the extra step to achieve disarmament peacefully."[73]

Additional justifications used at various times included Iraqi violation of UN resolutions, the Iraqi government's repression of its citizens, and Iraqi violations of the 1991 cease-fire.[21]

The main allegations were that Hussein possessed or was attempting to produce weapons of mass destruction which Saddam Hussein, had used such as in Halabja,[74][75] possessed, and made efforts to acquire. Particularly considering two previous attacks on Baghdad nuclear weapons production facilities by both Iran and Israel which was alleged to have postponed weapons development progress. And that he had ties to terrorists, specifically al-Qaeda.

While it never made an explicit connection between Iraq and the 11 September attacks, the George W. Bush administration repeatedly insinuated a link, thereby creating a false impression for the U.S. public. Grand jury testimony from the 1993 World Trade Center attack trials cited numerous direct linkages from the bombers to Baghdad and Department 13 of the Iraqi Intelligence Service in that initial attack marking the second anniversary to vindicate the surrender of Iraqi armed forces in Operation Desert Storm. For example, The Washington Post has noted that,

|

“ |

While not explicitly declaring Iraqi culpability in the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, administration officials did, at various times, imply a link. In late 2001, Cheney said it was "pretty well confirmed" that attack mastermind Mohamed Atta had met with a senior Iraqi intelligence official. Later, Cheney called Iraq the "geographic base of the terrorists who had us under assault now for many years, but most especially on 9/11."[76] |

” |

Steven Kull, director of the Program on International Policy Attitudes (PIPA) at the University of Maryland, observed in March 2003 that "The administration has succeeded in creating a sense that there is some connection [between 11 Sept. and Saddam Hussein]". This was following a New York Times/CBS poll that showed 45% of Americans believing Saddam Hussein was "personally involved" in the 11 September atrocities. As the Christian Science Monitor observed at the time, while "Sources knowledgeable about U.S. intelligence say there is no evidence that Hussein played a role in the 11 Sept. attacks, nor that he has been or is currently aiding Al Qaeda... the White House appears to be encouraging this false impression, as it seeks to maintain American support for a possible war against Iraq and demonstrate seriousness of purpose to Hussein's regime." The CSM went on to report that, while polling data collected "right after 11 Sept. 2001" showed that only 3 percent mentioned Iraq or Saddam Hussein, by January 2003 attitudes "had been transformed" with a Knight Ridder poll showing that 44% of Americans believed "most" or "some" of the 11 September hijackers were Iraqi citizens.[77]

According to General Tommy Franks, the objectives of the invasion were, "First, end the regime of Saddam Hussein. Second, to identify, isolate and eliminate Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction. Third, to search for, to capture and to drive out terrorists from that country. Fourth, to collect such intelligence as we can related to terrorist networks. Fifth, to collect such intelligence as we can related to the global network of illicit weapons of mass destruction. Sixth, to end sanctions and to immediately deliver humanitarian support to the displaced and to many needy Iraqi citizens. Seventh, to secure Iraq’s oil fields and resources, which belong to the Iraqi people. And last, to help the Iraqi people create conditions for a transition to a representative self-government.”[78]

The BBC has also noted that while President Bush, "never directly accused the former Iraqi leader of having a hand in the attacks on New York and Washington", he, "repeatedly associated the two in keynote addresses delivered since 11 September", adding that, "Senior members of his administration have similarly conflated the two." For instance, the BBC report quotes Colin Powell in February 2003, stating that, "We've learned that Iraq has trained al-Qaeda members in bomb-making and poisons and deadly gases. And we know that after September 11, Saddam Hussein's regime gleefully celebrated the terrorist attacks on America." The same BBC report also noted the results of a recent opinion poll, which suggested that "70% of Americans believe the Iraqi leader was personally involved in the attacks."[79]

Also in September 2003, the Boston Globe reported that "Vice President Dick Cheney, anxious to defend the White House foreign policy amid ongoing violence in Iraq, stunned intelligence analysts and even members of his own administration this week by failing to dismiss a widely discredited claim: that Saddam Hussein might have played a role in the 11 Sept. attacks."[80] A year later, presidential candidate John Kerry alleged that Cheney was continuing "to intentionally mislead the American public by drawing a link between Saddam Hussein and 9/11 in an attempt to make the invasion of Iraq part of the global war on terror."[81]

Throughout 2002, the Bush administration insisted that removing Hussein from power to restore international peace and security was a major goal. The principal stated justifications for this policy of "regime change" were that Iraq's continuing production of weapons of mass destruction and known ties to terrorist organizations, as well as Iraq's continued violations of UN Security Council resolutions, amounted to a threat to the U.S. and the world community.

Colin Powell holding a model vial of

anthrax while giving presentation to the United Nations Security Council on 5 February 2003 (still photograph captured from video clip, The White House/CNN)

The Bush administration's overall rationale for the invasion of Iraq was presented in detail by U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell to the United Nations Security Council on 5 February 2003. In summary, he stated,

|

“ |

We know that Saddam Hussein is determined to keep his weapons of mass destruction; he's determined to make more. Given Saddam Hussein's history of aggression... given what we know of his terrorist associations and given his determination to exact revenge on those who oppose him, should we take the risk that he will not some day use these weapons at a time and the place and in the manner of his choosing at a time when the world is in a much weaker position to respond? The United States will not and cannot run that risk to the American people. Leaving Saddam Hussein in possession of weapons of mass destruction for a few more months or years is not an option, not in a post–September 11 world.[82] |

” |

Since the invasion, the U.S. and British government statements concerning Iraqi weapons programs and links to terrorist organizations have been discredited. While the debate of whether Iraq intended to develop chemical, biological, and nuclear weapons in the future remains open, no WMDs have been found in Iraq since the invasion despite comprehensive inspections lasting more than 18 months.[83] In Cairo, on 24 February 2001, Colin Powell had predicted as much, saying, "[Hussein] has not developed any significant capability with respect to weapons of mass destruction. He is unable to project conventional power against his neighbours."[84] Similarly, assertions of operational links between the Iraqi regime and al-Qaeda have largely been discredited by the intelligence community, and Secretary Powell himself later admitted he had no proof.[85]

In September 2002, the Bush administration said attempts by Iraq to acquire thousands of high-strength aluminum tubes pointed to a clandestine program to make enriched uranium for nuclear bombs. Powell, in his address to the UN Security Council just before the war, referred to the aluminum tubes. A report released by the Institute for Science and International Security in 2002, however, reported that it was highly unlikely that the tubes could be used to enrich uranium. Powell later admitted he had presented an inaccurate case to the United Nations on Iraqi weapons, based on sourcing that was wrong and in some cases "deliberately misleading."[86][87][88]

The Bush administration asserted that the Hussein government had sought to purchase yellowcake uranium from Niger.[89] On 7 March 2003, the U.S. submitted intelligence documents as evidence to the International Atomic Energy Agency. These documents were dismissed by the IAEA as forgeries, with the concurrence in that judgment of outside experts. At the time, a US official stated that the evidence was submitted to the IAEA without knowledge of its provenance and characterized any mistakes as "more likely due to incompetence not malice".

Iraqi drones

In October 2002, a few days before the US Senate vote on the Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Iraq Resolution, about 75 senators were told in closed session that the Iraqi government had the means of delivering biological and chemical weapons of mass destruction by unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) drones that could be launched from ships off the US' Atlantic coast to attack US eastern seaboard cities. Colin Powell suggested in his presentation to the United Nations that UAVs were transported out of Iraq and could be launched against the United States. In fact, Iraq had no offensive UAV fleet or any capability of putting UAVs on ships.[90] Iraq's UAV fleet consisted of less than a handful of outdated Czech training drones.[91] At the time, there was a vigorous dispute within the intelligence community whether the CIA's conclusions about Iraq's UAV fleet were accurate. The US Air Force agency denied outright that Iraq possessed any offensive UAV capability.[92]

Human rights

As evidence supporting U.S. and British charges about Iraqi WMDs and links to terrorism weakened, some supporters of the invasion have increasingly shifted their justification to the human rights violations of the Hussein government.[93] Leading human rights groups such as Human Rights Watch have argued, however, that they believe human rights concerns were never a central justification for the invasion, nor do they believe that military intervention was justifiable on humanitarian grounds, most significantly because "the killing in Iraq at the time was not of the exceptional nature that would justify such intervention."[94]

Legality of invasion

The Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Iraq Resolution of 2002 was passed by congress with Republicans voting 98% in favor in the Senate, and 97% in favor in the House. Democrats supported the joint resolution 58% and 39% in the Senate and House respectively.[95][96] The resolution asserts the authorization by the Constitution of the United States and the Congress for the President to fight anti-United States terrorism. Citing the Iraq Liberation Act of 1998, the resolution reiterated that it should be the policy of the United States to remove the Saddam Hussein regime and promote a democratic replacement.

The resolution "supported" and "encouraged" diplomatic efforts by President George W. Bush to "strictly enforce through the U.N. Security Council all relevant Security Council resolutions regarding Iraq" and "obtain prompt and decisive action by the Security Council to ensure that Iraq abandons its strategy of delay, evasion, and noncompliance and promptly and strictly complies with all relevant Security Council resolutions regarding Iraq." The resolution authorized President Bush to use the Armed Forces of the United States "as he determines to be necessary and appropriate" to "defend the national security of the United States against the continuing threat posed by Iraq; and enforce all relevant United Nations Security Council Resolutions regarding Iraq."

The legality of the invasion of Iraq has been challenged since its inception on a number of fronts, and several prominent supporters of the invasion in all the invading nations have publicly and privately cast doubt on its legality. It is argued that the invasion was fully legal because authorization was implied by the United Nations Security Council.[97][98] International legal experts, including the International Commission of Jurists, a group of 31 leading Canadian law professors, and the U.S.-based Lawyers Committee on Nuclear Policy, have denounced both of these rationales.[99][100][101]

On Thursday 20 November 2003, an article published in the Guardian alleged that Richard Perle, a senior member of the administration's Defense Policy Board Advisory Committee, conceded that the invasion was illegal but still justified.[102][103]

The United Nations Security Council has passed nearly 60 resolutions on Iraq and Kuwait since Iraq's invasion of Kuwait in 1990. The most relevant to this issue is Resolution 678, passed on 29 November 1990. It authorizes "member states co-operating with the Government of Kuwait... to use all necessary means" to (1) implement Security Council Resolution 660 and other resolutions calling for the end of Iraq's occupation of Kuwait and withdrawal of Iraqi forces from Kuwaiti territory and (2) "restore international peace and security in the area." Resolution 678 has not been rescinded or nullified by succeeding resolutions and Iraq was not alleged after 1991 to invade Kuwait or to threaten do so.

Resolution 1441 was most prominent during the run up to the war and formed the main backdrop for Secretary of State Colin Powell's address to the Security Council one month before the invasion.[104] According to an independent commission of inquiry set up by the government of the Netherlands, UN resolution 1441 "cannot reasonably be interpreted (as the Dutch government did) as authorising individual member states to use military force to compel Iraq to comply with the Security Council's resolutions." Accordingly, the Dutch commission concluded that the 2003 invasion violated international law.[105]

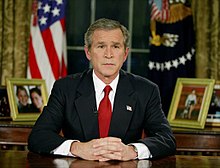

President George W. Bush

addresses the nation from the Oval Office, 19 March 2003, to announce the beginning of Operation Iraqi Freedom.

"The people of the United States and our friends and allies will not live at the mercy of an outlaw regime that threatens the peace with weapons of mass murder." The Senate committee found that many of the administration's pre-war statements about Iraqi WMD were not supported by the underlying intelligence

At the same time, Bush Administration officials advanced a parallel legal argument using the earlier resolutions, which authorized force in response to Iraq's 1990 invasion of Kuwait. Under this reasoning, by failing to disarm and submit to weapons inspections, Iraq was in violation of U.N. Security Council Resolutions 660 and 678, and the U.S. could legally compel Iraq's compliance through military means.

Critics and proponents of the legal rationale based on the U.N. resolutions argue that the legal right to determine how to enforce its resolutions lies with the Security Council alone, not with individual nations.

In February 2006, Luis Moreno Ocampo, the lead prosecutor for the International Criminal Court, reported that he had received 240 separate communications regarding the legality of the war, many of which concerned British participation in the invasion.[106] In a letter addressed to the complainants, Mr. Moreno Ocampo explained that he could only consider issues related to conduct during the war and not to its underlying legality as a possible crime of aggression because no provision had yet been adopted which "defines the crime and sets out the conditions under which the Court may exercise jurisdiction with respect to it." In a March 2007 interview with the Sunday Telegraph, Moreno Ocampo encouraged Iraq to sign up with the court so that it could bring cases related to alleged war crimes.[107]

United States Ohio Congressman Dennis Kucinich held a press conference on the evening of 24 April 2007, revealing US House Resolution 333 and the three articles of impeachment against Vice President Dick Cheney. He charged Cheney with manipulating the evidence of Iraq's weapons program, deceiving the nation about Iraq's connection to al-Qaeda, and threatening aggression against Iran in violation of the United Nations Charter.

Military aspects

United States military operations were conducted under the codename Operation Iraqi Liberation (OIL).[108] The codename was later changed to Operation Iraqi Freedom, due to the unfortunate acronym. The United Kingdom military operation was named Operation Telic.

Multilateral support

In November 2002, President George W. Bush, visiting Europe for a NATO summit, declared that, "should Iraqi President Saddam Hussein choose not to disarm, the United States will lead a coalition of the willing to disarm him."[109]

Thereafter, the Bush administration briefly used the term Coalition of the Willing to refer to the countries who supported, militarily or verbally, the military action in Iraq and subsequent military presence in post-invasion Iraq since 2003. The original list prepared in March 2003 included 49 members.[110] Of those 49, only six besides the U.S. contributed troops to the invasion force (the United Kingdom, Spain, Australia, Poland, Portugal, and Denmark), 33 provided some number of troops to support the occupation after the invasion was complete. Six members have no military.

Invasion force

Approximately 148,000 soldiers from the United States, 45,000 British soldiers, 2,000 Australian soldiers and 194 Polish soldiers from the special forces unit GROM were sent to Kuwait for the invasion.[111] The invasion force was also supported by Iraqi Kurdish militia troops, estimated to number upwards of 70,000.[9] In the latter stages of the invasion 620 troops of the Iraqi National Congress opposition group were deployed to southern Iraq.[3]

A U.S. Central Command, Combined Forces Air Component Commander report, indicated that as of 30 April 2003, there were a total of 466,985 U.S. personnel deployed for Operation Iraqi Freedom. This included USAF, 54,955; USAF Reserve, 2,084; Air National Guard, 7,207; USMC, 74,405; USMC Reserve, 9,501; USN, 61,296 (681 are members of the U.S. Coast Guard); USN Reserve, 2,056; and US Army, 233,342; US Army Reserve, 10,683; and Army National Guard, 8,866.[112]

Plans for opening a second front in the north were severely hampered when Turkey refused the use of its territory for such purposes.[113] In response to Turkey's decision, the United States dropped several thousand paratroopers from the 173rd Airborne Brigade into northern Iraq, a number significantly less than the 15,000-strong 4th Infantry Division that the U.S. originally planned to use for opening the northern front.[114]

Preparation

CIA Special Activities Division (SAD) Paramilitary teams entered Iraq in July 2002 before the 2003 invasion. Once on the ground they prepared for the subsequent arrival of US military forces. SAD teams then combined with US Army Special Forces to organize the Kurdish Peshmerga. This joint team combined to defeat Ansar al-Islam, an ally of Al Qaida, in a battle in the northeast corner of Iraq. The US side was carried out by Paramilitary Officers from SAD and the Army's 10th Special Forces Group.[54][55][56]

SAD teams also conducted high risk special reconnaissance missions behind Iraqi lines to identify senior leadership targets. These missions led to the initial strikes against Saddam Hussein and his key generals. Although the initial strikes against Hussein were unsuccessful in killing the dictator or his generals, it was successful in effectively ending the ability to command and control Iraqi forces. Other strikes against key generals were successful and significantly degraded the command's ability to react to and maneuver against the U.S.-led invasion force coming from the south.[54][56]

SAD operations officers were also successful in convincing key Iraqi army officers to surrender their units once the fighting started and/or not to oppose the invasion force.[55] NATO member Turkey refused to allow its territory to be used for the invasion. As a result, the SAD/SOG and US Army Special Forces joint teams and the Kurdish Peshmerga were the entire northern force against government forces during the invasion. Their efforts kept the 5th Corps of the Iraqi army in place to defend against the Kurds rather than their moving to contest the coalition force.

According to General Tommy Franks, April Fool, an American officer working undercover as a diplomat, was approached by an Iraqi intelligence agent. April Fool then sold to the Iraqi false "top secret" invasion plans provided by Franks' team. This decoy deception successfully misled the Iraqi military into deploying major forces in Northern and Western Iraq in anticipation of attacks by way of Turkey or Jordan, which never took place. This greatly reduced the defensive capacity in the rest of Iraq and significantly facilitated the actual attacks via Kuwait and the Persian Gulf in the southeast.

Defending force

The number of personnel in the Iraqi military prior to the war was uncertain, but it was believed to have been poorly equipped.[115][116][117] The International Institute for Strategic Studies estimated the Iraqi armed forces to number 538,000 (Iraqi Army 375,000, Iraqi Navy 2,000, Iraqi Air Force 20,000 and air defense 17,000), the paramilitary Fedayeen Saddam 44,000, Republican Guard 80,000 and reserves 650,000.[118]

Another estimate numbers the Army and Republican Guard at between 280,000 to 350,000 and 50,000 to 80,000, respectively,[119] and the paramilitary between 20,000 and 40,000.[120] There were an estimated thirteen infantry divisions, ten mechanized and armored divisions, as well as some special forces units. The Iraqi Air Force and Navy played a negligible role in the conflict.

During the invasion, foreign volunteers traveled to Iraq from Syria and took part in the fighting, usually under the command of the Fedayeen Saddam. It is not known for certain how many foreign fighters fought in Iraq in 2003, however, intelligence officers of the U.S. First Marine Division estimated that 50% of all Iraqi combatants in central Iraq were foreigners.[121][122]

In addition, the Kurdish Islamist militant group Ansar al-Islam controlled a small section of northern Iraq in an area outside of Saddam Hussein's control. Ansar al-Islam had been fighting against secular Kurdish forces since 2001. At the time of the invasion they fielded approximately 600 to 800 fighters.[123] Ansar al-Islam was led by the Jordanian-born militant Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, who would later become an important leader in the Iraqi insurgency. Ansar al-Islam was driven out of Iraq in late March by a joint American-Kurdish force during Operation Viking Hammer.

Invasion

US invasion: 20–28 March 2003

US invasion: 29 March – 7 April 2003

Routes and major battles fought by invasion force and afterwards

Since the 1991 Gulf War, the U.S. and UK had been engaged in low-level attacks on Iraqi air defenses which targeted them while enforcing Iraqi no-fly zones.[35][36] These zones, and the attacks to enforce them, were described as illegal by the former UN Secretary General, Boutros Boutros-Ghali, and the French foreign minister Hubert Vedrine. Other countries, notably Russia and China, also condemned the zones as a violation of Iraqi sovereignty.[124][125][126] In mid-2002, the U.S. began more carefully selecting targets in the southern part of the country to disrupt the military command structure in Iraq. A change in enforcement tactics was acknowledged at the time, but it was not made public that this was part of a plan known as Operation Southern Focus.

The amount of ordnance dropped on Iraqi positions by Coalition aircraft in 2001 and 2002 was less than in 1999 and 2000 which was during the Clinton administration.[127] This information has been used to attempt to refute the theory that the Bush administration had already decided to go to war against Iraq before coming to office and that the bombing during 2001 and 2002 was laying the groundwork for the eventual invasion in 2003. However, information obtained by the UK Liberal Democrats showed that the UK dropped twice as many bombs on Iraq in the second half of 2002 as they did during the whole of 2001. The tonnage of UK bombs dropped increased from 0 in March 2002 and 0.3 in April 2002 to between 7 and 14 tons per month in May–August, reaching a pre-war peak of 54.6 tons in September – before Congress' 11 October authorization of the invasion.

The 5 September attacks included a 100+ aircraft attack on the main air defense site in western Iraq. According to an editorial in New Statesman this was "Located at the furthest extreme of the southern no-fly zone, far away from the areas that needed to be patrolled to prevent attacks on the Shias, it was destroyed not because it was a threat to the patrols, but to allow allied special forces operating from Jordan to enter Iraq undetected."[128]

Tommy Franks, who commanded the invasion of Iraq, has since admitted that the bombing was designed to "degrade" Iraqi air defences in the same way as the air attacks that began the 1991 Gulf War. These "spikes of activity" were, in the words of then British Defence Secretary, Geoff Hoon, designed to 'put pressure on the Iraqi regime' or, as The Times reported, to "provoke Saddam Hussein into giving the allies an excuse for war". In this respect, as provocations designed to start a war, leaked British Foreign Office legal advice concluded that such attacks were illegal under international law.[129][130]

Another attempt at provoking the war was mentioned in a leaked memo from a meeting between George W. Bush and Tony Blair on 31 January 2003 at which Bush allegedly told Blair that "The US was thinking of flying U2 reconnaissance aircraft with fighter cover over Iraq, painted in UN colours. If Saddam fired on them, he would be in breach."[131] On 17 March 2003, U.S. President George W. Bush gave Saddam Hussein 48 hours to leave the country, along with his sons Uday and Qusay, or face war.

Opening salvo: the Dora Farms strike

On the early morning of 19 March 2003, U.S. forces abandoned the plan for initial, non-nuclear decapitation strikes against 55 top Iraqi officials, in light of reports that Saddam Hussein was visiting his sons, Uday and Qusay, at Dora Farms, within the al-Dora farming community on the outskirts of Baghdad.[132] At approximately 05:30 UTC two F-117 Nighthawks from the 8th Expeditionary Fighter Squadron[133] dropped four enhanced, satellite-guided 2,000-pound GBU-27 'Bunker Busters' on the compound. Complementing the aerial bombardment were nearly 40 Tomahawk cruise missiles fired from at least four ships, including the Arleigh Burke-class destroyer USS Donald Cook (DDG-75), and two submarines in the Red Sea and Persian Gulf.[134]

One bomb missed the compound entirely and the other three missed their target, landing on the other side of the wall of the palace compound.[135] Saddam Hussein was not present nor were any members of the Iraqi leadership.[132][136] The attack killed one civilian and injured fourteen others, including four men, nine women and one child.[137][138] Later investigation revealed that Saddam Hussein had not visited the farm since 1995.[134]

Opening attack

On 20 March 2003 at approximately 02:30 UTC or about 90 minutes after the lapse of the 48-hour deadline, at 05:33 local time, explosions were heard in Baghdad. Special operations commandos from the CIA's Special Activities Division from the Northern Iraq Liaison Element infiltrated throughout Iraq and called in the early air strikes.[54] At 03:15 UTC, or 10:15 pm EST, George W. Bush announced that he had ordered an "attack of opportunity" against targets in Iraq.[139] When this word was given, the troops on standby crossed the border into Iraq.

Wingtip vortices are visible trailing from an

F-15E as it disengages from midair refueling with a

KC-10 during Operation Iraqi Freedom

Before the invasion, many observers had expected a lengthy campaign of aerial bombing before any ground action, taking as examples the 1991 Persian Gulf War or the 2001 invasion of Afghanistan. In practice, U.S. plans envisioned simultaneous air and ground assaults to decapitate the Iraqi forces quickly (see Shock and Awe), attempting to bypass Iraqi military units and cities in most cases. The assumption was that superior mobility and coordination of Coalition forces would allow them to attack the heart of the Iraqi command structure and destroy it in a short time, and that this would minimize civilian deaths and damage to infrastructure. It was expected that the elimination of the leadership would lead to the collapse of the Iraqi Forces and the government, and that much of the population would support the invaders once the government had been weakened. Occupation of cities and attacks on peripheral military units were viewed as undesirable distractions.

Following Turkey's decision to deny any official use of its territory, the Coalition was forced to modify the planned simultaneous attack from north and south.[140] Special Operations forces from the CIA and US Army managed to build and lead the Kurdish Peshmerga into an effective force and assault for the North. The primary bases for the invasion were in Kuwait and other Persian Gulf nations. One result of this was that one of the divisions intended for the invasion was forced to relocate and was unable to take part in the invasion until well into the war. Many observers felt that the Coalition devoted sufficient numbers of troops to the invasion, but too many were withdrawn after it ended, and that the failure to occupy cities put them at a major disadvantage in achieving security and order throughout the country when local support failed to meet expectations.

NASA Landsat 7 image of

Baghdad, 2 April 2003. The dark streaks are smoke from oil well fires set in an attempt to hinder attacking air forces

The invasion was swift, leading to the collapse of the Iraqi government and the military of Iraq in about three weeks. The oil infrastructure of Iraq was rapidly seized and secured with limited damage in that time. Securing the oil infrastructure was considered of great importance. In the Gulf War, while retreating from Kuwait, the Iraqi army had set many oil wells on fire in an attempt to disguise troop movements and to distract Coalition forces. Before the 2003 invasion, Iraqi forces had mined some 400 oil wells around Basra and the Al-Faw peninsula with explosives. Coalition troops launched an air and amphibious assault on the Al-Faw peninsula during the closing hours of 19 March to secure the oil fields there; the amphibious assault was supported by warships of the Royal Navy, Polish Navy, and Royal Australian Navy.

British 3 Commando Brigade, with the United States Marine Corps' 15th Marine Expeditionary Unit and the Polish Special Forces unit GROM attached, attacked the port of Umm Qasr. There they met with heavy resistance by Iraqi troops. A total of 14 Coalition troops and 30–40 Iraqi troops were killed, and 450 Iraqis taken prisoner. The British Army's 16 Air Assault Brigade also secured the oil fields in southern Iraq in places like Rumaila while the Polish commandos captured offshore oil platforms near the port, preventing their destruction. Despite the rapid advance of the invasion forces, some 44 oil wells were destroyed and set ablaze by Iraqi explosives or by incidental fire. However, the wells were quickly capped and the fires put out, preventing the ecological damage and loss of oil production capacity that had occurred at the end of the Gulf War.

In keeping with the rapid advance plan, the U.S. 3rd Infantry Division moved westward and then northward through the western desert toward Baghdad, while the 1st Marine Expeditionary Force moved along Highway 1 through the center of the country, and 1 (UK) Armoured Division moved northward through the eastern marshland.

During the first week of the war, Iraqi forces fired a Scud missile at the American Battlefield Update Assessment center in Camp Doha, Kuwait. The missile was intercepted and shot down by a Patriot missile seconds before hitting the complex. Subsequently, two A-10 Warthogs bombed the missile launcher.

Battle of Nasiriyah

Initially, the U.S. 1st Marine Division fought through the Rumaila oil fields, and moved north to Nasiriyah—a moderate-sized, Shi'ite dominated city with important strategic significance as a major road junction and its proximity to nearby Talil Airfield. It was also situated near a number of strategically important bridges over the Euphrates River. The city was defended by a mix of regular Iraqi army units, Ba'ath loyalists, and Fedayeen from both Iraq and abroad. The United States Army 3rd Infantry Division defeated Iraqi forces entrenched in and around the airfield and bypassed the city to the west.

A U.S. amphibious fighting vehicle destroyed near Nasiriyah

On 23 March, a convoy from the 3rd Infantry Division, including the female American soldiers Jessica Lynch and Lori Piestewa, was ambushed after taking a wrong turn into the city. Eleven U.S. soldiers were killed, and seven, including Lynch and Piestewa, were captured.[141] Piestewa died of wounds shortly after capture, while the remaining five prisoners of war were later rescued. Piestewa, who was from Tuba City, Arizona, and an enrolled member of the Hopi Tribe, was believed to have been the first Native American woman killed in combat in a foreign war. On the same day, U.S Marines from the Second Marine Division entered Nasiriyah in force, facing heavy resistance as they moved to secure two major bridges in the city. Several Marines were killed during a firefight with Fedayeen in the urban fighting. At the Saddam Canal, another 18 Marines were killed in heavy fighting with Iraqi soldiers. An Air Force A-10 was involved in a case of friendly fire that resulted in the death of six Marines when it accidentally attacked an American amphibious vehicle. Two other vehicles were destroyed when a barrage of RPG and small arms fire killed most of the Marines inside.[142] A Marine from Marine Air Control Group 28 was killed by enemy fire, and two Marine engineers drowned in the Saddam Canal. The bridges were secured and the Second Marine division set up an perimeter around the city.

A U.S. soldier stands guard duty near a burning oil well in the

Rumaila oil field, 2 April 2003

On the evening of 24 March, a battalion of the 1st Marine Regiment pushed through Nasiriyah and established a perimeter 15 kilometers (9.3 miles) north of the city. Iraqi reinforcements from Kut launched several counterattacks. The Marines managed to repel them using indirect fire and close air support. The last Iraqi attack was beaten off at dawn. The battalion estimated that 200–300 Iraqi soldiers were killed, without a single U.S. casualty. Nasiriyah was declared secure, but attacks by Iraqi Fedayeen continued. These attacks were uncoordinated, and resulted in firefights in which large numbers of Fedayeen were killed. Because of Nasiriyah's strategic position as a road junction, a significant gridlock occurred as U.S. forces moving north converged on the city's surrounding highways.

With the Nasiriyah and Talil Airfields secured, Coalition forces gained an important logistical center in southern Iraq and established FOB/EAF Jalibah, some 10 miles (16 km) outside of Nasiriyah. Additional troops and supplies were soon brought through this forward operating base. The 101st Airborne Division continued its attack north in support of the 3rd Infantry Division.

By 28 March, a severe sand storm slowed the Coalition advance as the 3rd Infantry Division halted its northward drive half way between Najaf and Karbala. As a result of heavy rains that occurred along with the sand storm, orange-colored mud fell on some parts of the invasion force in the area. Air operations by helicopters, poised to bring reinforcements from the 101st Airborne, were blocked for three days. There was particularly heavy fighting in and around the bridge near the town of Kufl.

Continued on page 3

| Author: | Bling King |

| Published: | Mar 24th 2013 |

| Modified: | Mar 24th 2013 |